New Horizons and Pluto

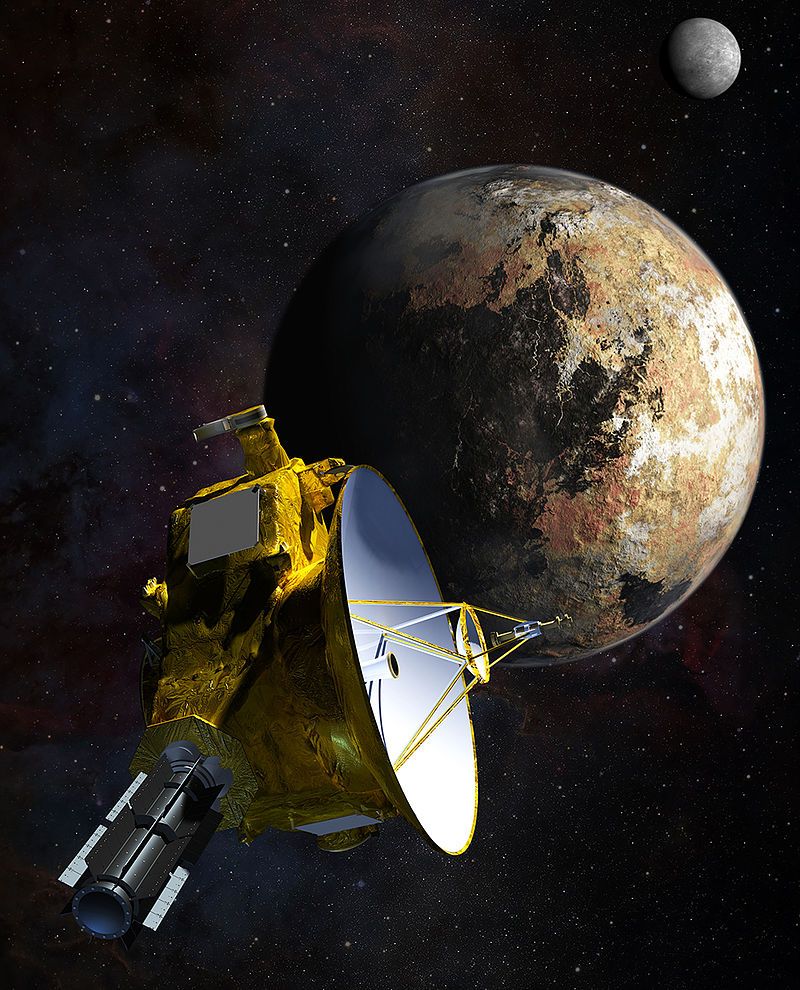

The objective of the NASA mission, New Horizons, was to study Pluto, its moons, and other objects in the Kuiper Belt. New Horizons was the first mission in the New Frontiers program, a competitively selected, medium-class, and principal investigator-led series of missions. New Horizons was the first spacecraft to reach Pluto, a relic from the solar system's formation. By the time it reached Pluto, the spacecraft had traveled for a longer period and farther away than any previous deep-space spacecraft ever launched.

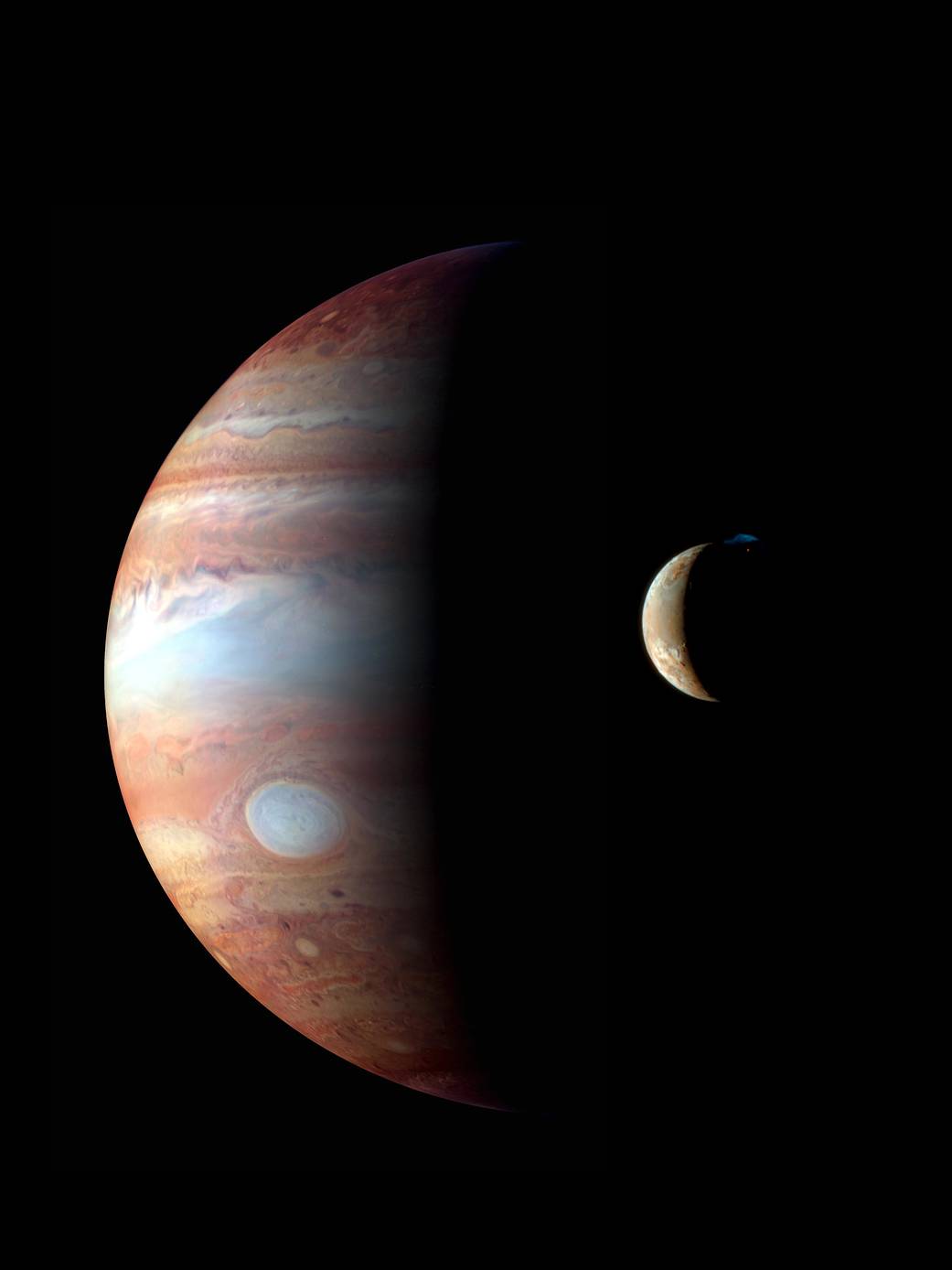

New Horizons launched from Cape Canaveral on January 19, 2006, becoming the fastest human-made object ever launched from Earth. It was put directly into an Earth-and-solar escape trajectory with a speed of about 16.26 km/s (10.10 mi/s). Controllers implemented course corrections through January and March of that year, and on April 7, 2006, New Horizons passed the orbit of Mars. An opportunity arose to test the spacecraft's scientific instruments, especially Ralph, the visible and infrared imager and spectrometer, on June 13, when New Horizons passed by the tiny asteroid 132524 APL at a range of about 101,867 km (63,300 mi).

On March 12, 2015, with nearly four months remaining until its close encounter, the spacecraft finally got closer to Pluto than Earth is to the Sun. Pictures of Pluto taken in April 2015 revealed distinct features, and each picture that followed had increased detail as the distance between New Horizons and Pluto closed. On July 10, 2015, data collected was used to conclusively answer the mystery of Pluto's size! Scientists concluded that Pluto is about 2,370 km (1,470 mi) in diameter, making it slightly larger than previous estimations. Its moon, Charon, was subsequently confirmed to be about 1,208 km (750 mi) in diameter.

New Horizons was not only tasked with collecting data on Pluto and Charon, but on Pluto's other satellites, Hydra, Nix, Styx, and Kerberos. It took NASA over 15 months to download the entire data set collected during the Pluto, and Charon encounters. Despite how long this may seem, it was necessary considering the distance between Earth and New Horizons, and the spacecraft could only transmit 1-2 kilobits per second.

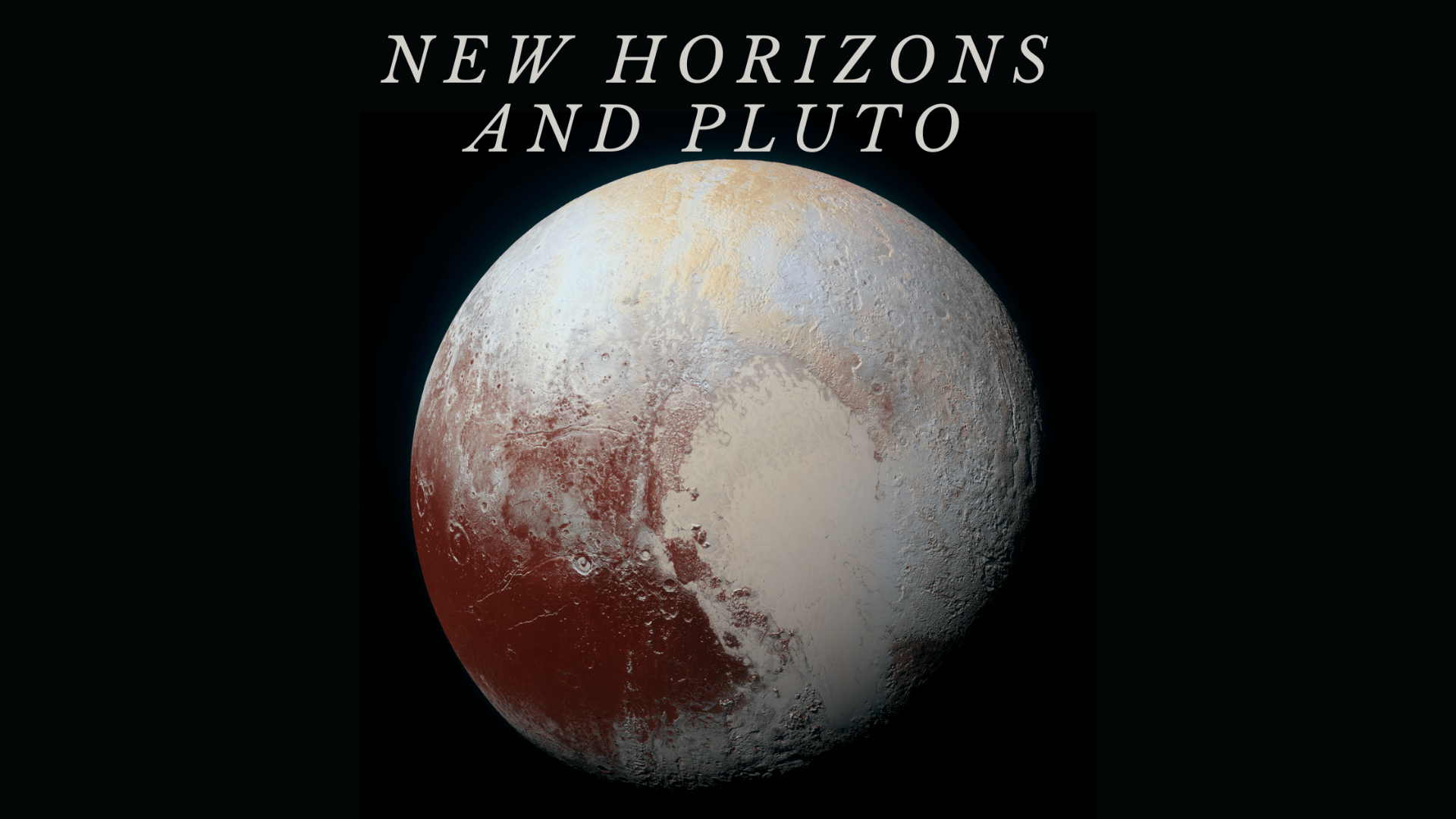

The data collected from New Horizons informed us that Pluto and its satellites are far more complicated we initially thought, and scientists were particularly surprised by the level of activity on Pluto's surface. The atmospheric haze and lower-than-predicted atmospheric escape rate forced scientists to revise earlier models of the system fundamentally. There was also evidence of intense shifts in atmospheric pressure, which lead to the possibility Pluto had standing or running liquid material on its surface in the past, or even now!

Stunning photographs showed a giant heart-shaped glacier made of nitrogen, named Sputnik Planitia, on Pluto's surface. The glacier is about 1,000-km wide (600 mi), making it undoubtedly the largest glacier in the solar system that we know of. Images of Charon showed a giant tectonic belt, further suggesting liquid on the surface of Pluto as a long-gone water/ice ocean.

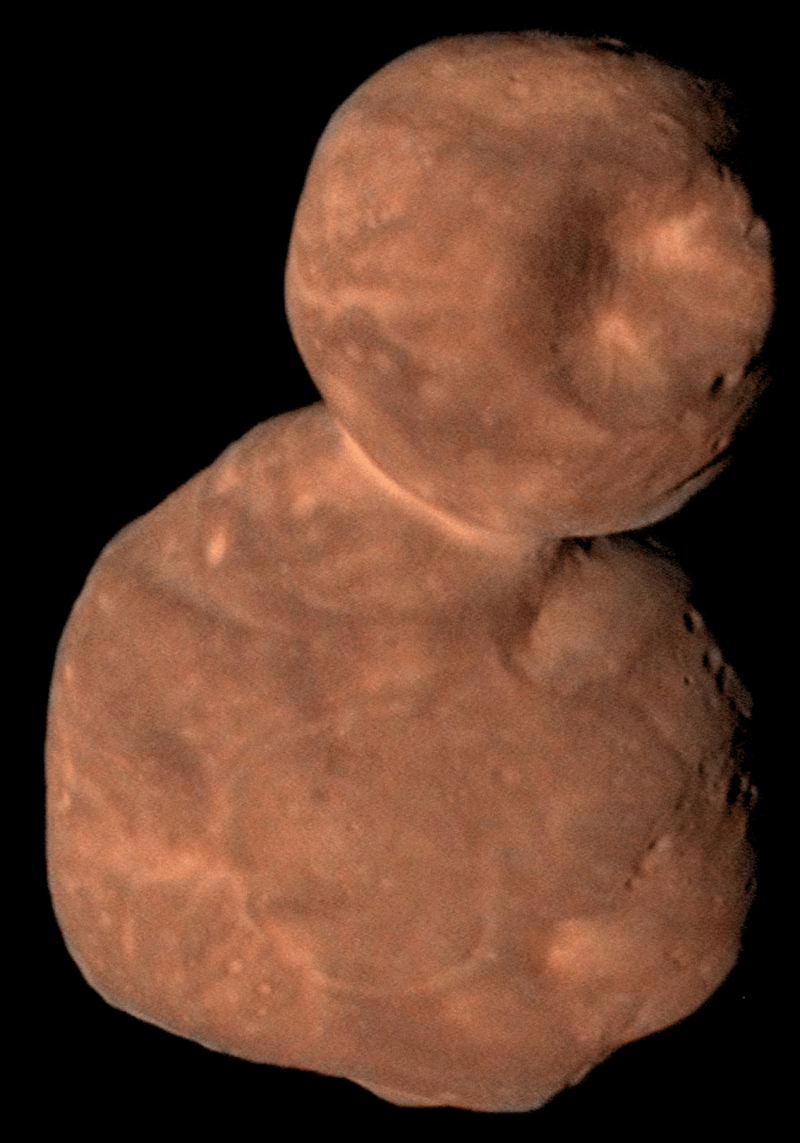

The spacecraft was halfway to its new target from Pluto on April 3, 2017, and soon after entered hibernation mode for "a long summer's nap" that lasted until September 11, 2017. On July 14, 2017, the anniversary of its Pluto-Charon flyby, the New Horizons team unveiled new detailed maps of both planetary bodies.

In terms of other scientific discoveries made possible by New Horizons, in August 2018, NASA confirmed the existence of a "hydrogen wall" with evidence from New Horizons at the outer edges of the Solar System. This "hydrogen wall" theory was first detected and proposed in 1992 by the Voyager spacecrafts. New Horizons was about 6.6 billion km (4.1 billion mi) from Earth, as of March 2019, and was operating normally and speeding deeper into the Kuiper Belt at nearly 53,000 km/h (33,000 mi/h). The New Horizons mission has been extended through 2021 to explore additional Kuiper Belt objects.